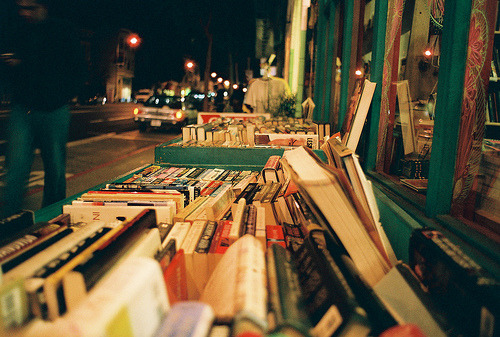

About three and a half years ago, I was seventeen, a senior in high school, and working my way through the final year of the International Baccalaureate degree. I was on the brink of college, thinking about what I wanted to do with my life and why, and utterly certain that, if nothing else, I loved books and the worlds that they opened for me, and I wanted to spend as much time around them (and around other people who thought this way about them) as I could.

Out of all the things I read for IB English, Jane Eyre is undoubtedly the one that has turned out to hold the greatest importance in my life — but second only to Jane Eyre is a slim, spare poem that had shown up on an IB English exam a few years back and was given to us as a practice text. It wasn't on our syllabus, we never really discussed it as a class, and we were supposed to give our copies of it back to the teacher once we’d finished with them.

I didn’t. I couldn’t. Because this poem reached out to me and didn’t let me go.

The Secret Life of BooksThey have their stratagems too, though they can’t move.

They know their parts.

Like invalids long reconciled

To stillness, they do their work through others.

They have turned the world

To their own account by the twisting of hearts.

What do they have to say and how do they say it?

In the library

At night, or the sun room with its one

Curled thriller by the window, something

Is going on,

You may suspect, that you don’t know of. Yet they

Need you. The time comes when you pick one up,

You who scoff

At determinism, the selfish gene.

Why this one? Look, already the blurb

Is drawing in

Some further text. The second paragraph

Calls for an atlas or a gazetteer;

That poem, spare

As a dead leaf’s skeleton, coaxes

Your lexicon. Through you they speak

As through the sexes

A script is passed that lovers never hear.

They have you. In the end they have written you,

By the intrusion

Of their account of the world, so when

You come to think, to tell, to do,

You’re caught between

Quotation marks, your heart’s beat an allusion.

Stephen Edgar, from Corrupted Treasures (1995)

Every time I read this poem, it makes me think in new and interesting ways about the relationships between books and their readers. Usually, every time I read it, I spend the first few stanzas feeling absolutely absorbed in the language used to describe the secret life of these books in question, the slim personification just enough for me to believe that they’re only alive when I’m not looking, or when I can just see them shuffle their covers out of the corner of my eye.

But by the time I make it to the final stanza, I start to develop this strange and disconcerting feeling in the region of my stomach. Because I am exactly the person “caught between / Quotation marks” in almost everything that I do, and far from it being accidental or unintentional (as the poet suggests this must be for most people) I do this all of the time on purpose. I use other peoples’ words when I can’t find my own. But then I start thinking: is this really true? Do I only quote when someone else has really said it better before, or do I sometimes let the quotations do my thinking for me, providing them as an educated response to a question or problem that I haven’t really managed to find a personal response to yet?

As a writer, this idea of being caught in constant quotation is even more of a chore: what does it say for the originality of anything I write creatively? I’ve often thought this is one of the largest problems I run into as someone who writes both creatively and analytically. Writing as an English major entails endless quotation, and values that quotation as the heart of the resulting text. My ideas about the text are important, but the text I produce in describing those ideas is often attributed back to the original text — even within my own writing, this happens. I may be clever to spot a pattern in Milton’s use of chiasmus or Austen’s depictions of reading, but the ultimate cleverness reverts back to Milton and Austen for embedding these things in their works in the first place (even if they have only done it unconsciously and I have excavated their meaning through conscious effort).

And then, when I’ve spent so much time with the words of others, exploring them, extracting them carefully from the text, coaxing them out inch by inch, and venerating them in the process, writing anything of my own seems not just silly but impossible. I have been written by all of the books I have ever read, so when it comes time for me to write books of my own, sometimes I’m afraid all I can do is re-write those books that have shaped me and hope no one notices the similarities.

Most of the time, I revel in my ability to quote my favorite texts, to carry them with me always. I think about the scene around the campfire at the end of Fahrenheit 451, with these men reciting literature against the darkness. But this poem makes me ask uncomfortable questions. It makes me think against the grain of the books that have written me over the years. Above all, it makes me reimagine that campfire circle: instead of these men preserving their past, they are stifling their future. Because isn’t it almost possible that by devoting themselves so wholly to the fictional creations of former ages, they are prevented from creating new (and possibly more relevant) fictions of their own?

Fiction is manipulative. This isn’t to say that it’s inherently good or bad, but it plays with my heartstrings and has the power to make me think ideas or do things or be someone that I wouldn’t have been without it. Sometimes, I forget that. Most of the time, I forget how ambivalent this power is. But this poem always reminds me.

Brava Candace Cunard, I found your blog post just now (well, time is a great loiterer on the web) looking for a link about this poem which I know pretty well having recorded Stephen Edgar reading it. Edgar continues to write brilliant poems - I hope you get a chance to read some of them.

ReplyDelete